US Customs and ocean liner travelers in the mid 20th century

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Michelle Kennedy, Collections and Curatorial Assistant

July 8, 2021

Imagine it is ca. 1950. You’ve just arrived in New York City on board one of the sleek, modern ocean liners of the era after a five-day voyage across the Atlantic ocean. Your ship has passed the lightship marking the entrance to the Ambrose Channel, sailed past the Statue of Liberty, and brought the Manhattan skyline into view as your vessel approaches its West Side pier. Similarly to international travellers in the 21st century, you now have a true test of patience as you disembark: you and your 2,000 or so fellow passengers have to try to locate your baggage and undergo a US Customs inspection.

Unlike international travellers in the 21st century, there are no baggage scanners, no luggage carousels, and no computer terminals for the Customs inspectors to consult. In order to efficiently process the thousands of incoming passengers and their thousands of trunks and bags, the Customs Service of the Port of New York has to pull out all the stops. This blog will explore how the Customs staff prepared for the arrival of a mid-century ocean liner using artifacts from the US Custom House Collection, on long-term loan to the South Street Seaport Museum from the National Archives in New York City.

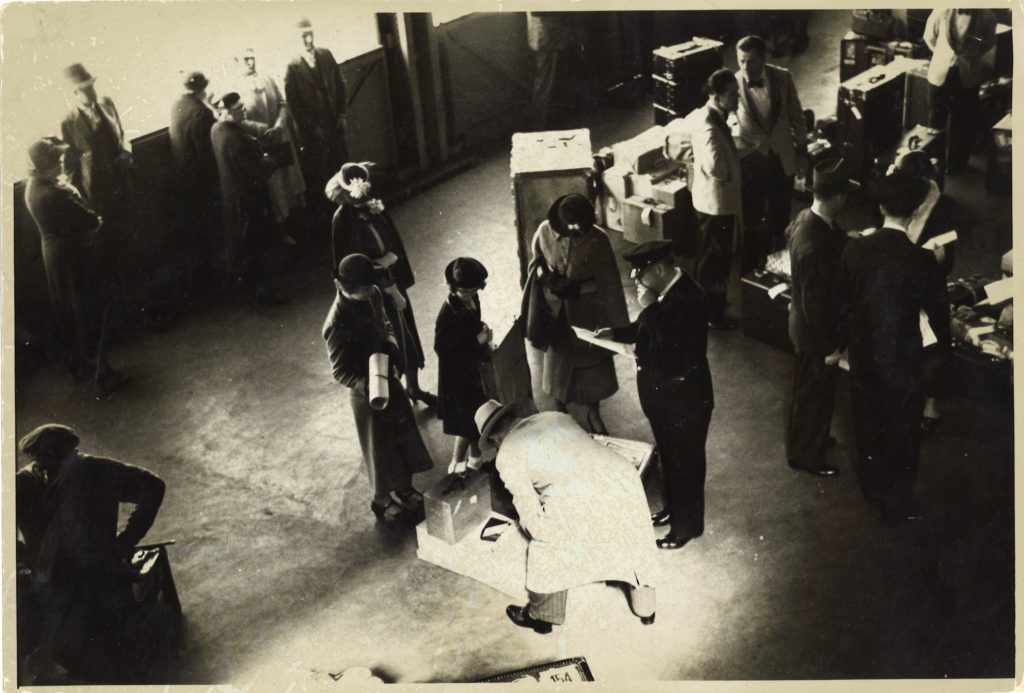

“Arrivals in Port of New York”, 1939. Photographic print. US Custom House Collection, 2005.USCH.0236

The Collection

The US Custom House Collection at the Seaport Museum is a fascinating selection of documents, photographs, and artifacts related to New York City’s Customs activity throughout the 20th century. Since Customs was responsible for tracking the entrance and clearance of all vessels, appraising merchandise, collecting revenue, and preventing smuggling of illegal articles, the episodes documented in the Collection paint a compelling picture of the New York waterfront. Topics include the smuggling of drugs and jewels, fires and collisions in the New York waterways, defending the Harbor during the World Wars, as well as the careful inspection of the various cargoes passing through one of the busiest ports in the world.

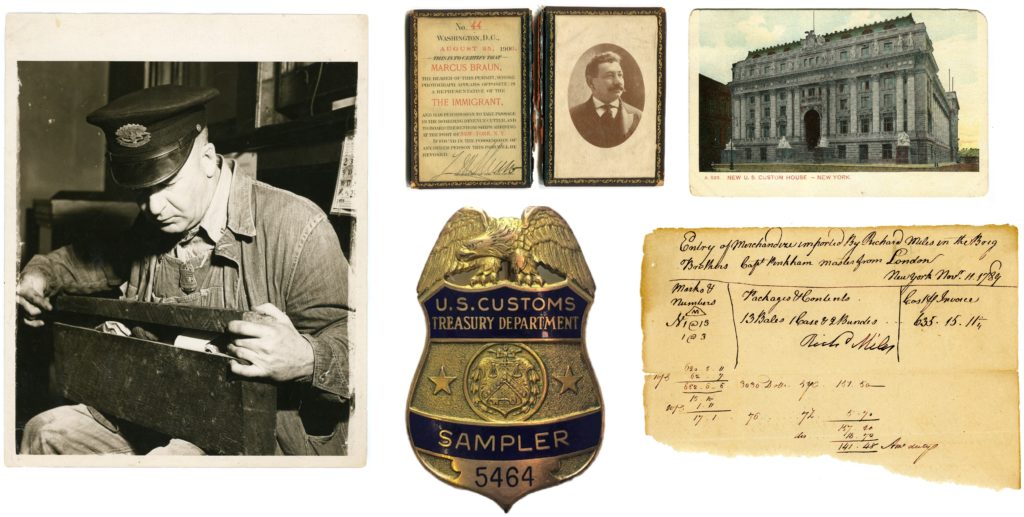

Items from the US Custom House Collection

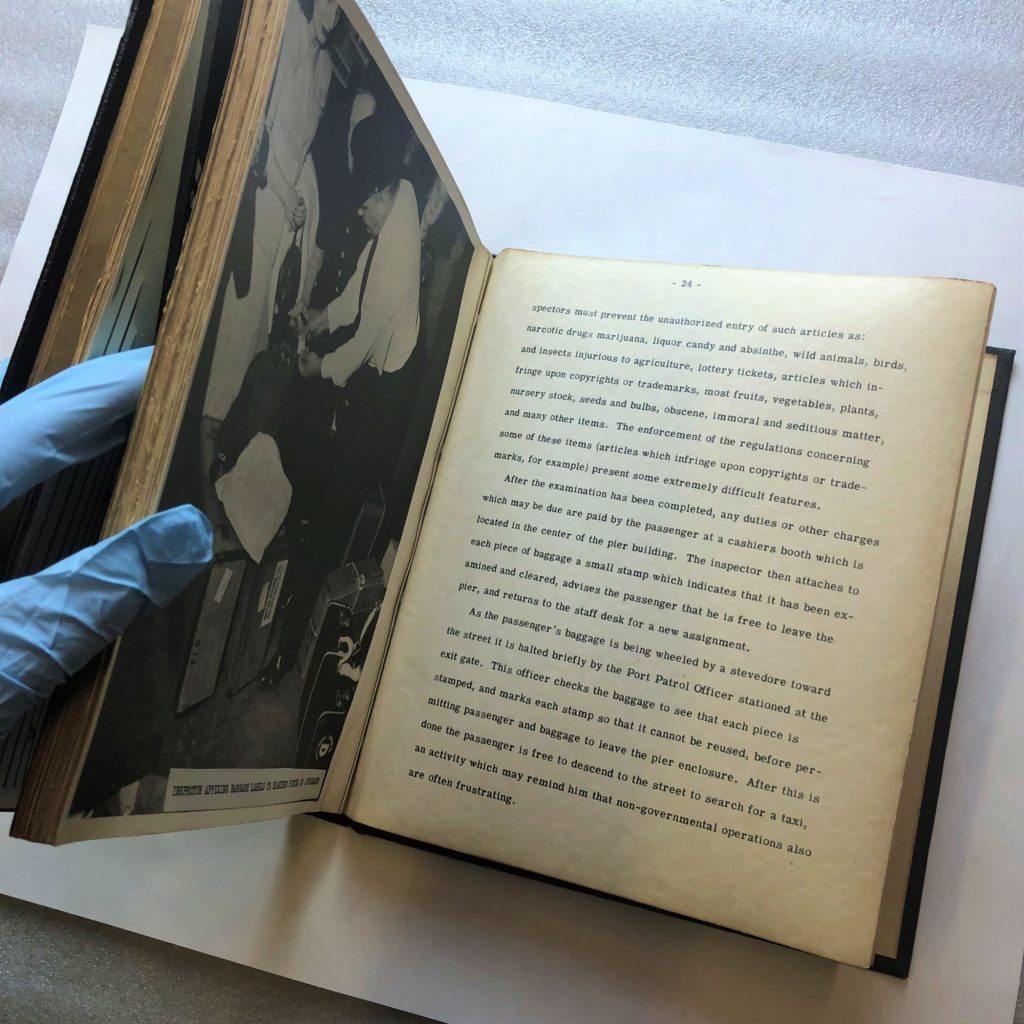

Since the collection includes both artifacts and a variety of archival material, there are many opportunities for researchers and cataloguers to cross-reference items. While researching how New York Customs handled the arrivals of massive ocean liners, I was able to look at photographs and documents that related to the same procedures. Much of the information for this blog came from a 1949 book in the collection titled Custom Inspection of Passenger Baggage. Published by the Customs of the Port of New York, this book is not strictly informational— it includes many long-suffering asides explaining why disembarking passengers needed to be patient with the US Customs inspectors and detailing the frustrations of being unfairly blamed for delays. With that in mind, let’s celebrate the logistical feat of securely unloading an ocean liner onto a New York City pier.

“Custom Inspection of Passenger Baggage”, July 15, 1949. Paper, ink, leather. US Custom House Collection, 1993.USCH.0008

Preparing for a Queen

The preparations for the arrival of the largest passenger ships of the mid 20th century started weeks in advance. Customs was responsible for every ship coming from across the world into the Port of New York from ocean liners to cargo ships to tankers. Since the volume of cargo traffic in the Port was greater and more constant than the volume of passenger traffic, Customs was organized around cargo as a daily priority. However, when a large passenger ship was scheduled, Customs inspectors from across the Harbor would be called in to handle the huge influx of people and luggage. Transatlantic ocean liners like the Cunard Line’s RMS Queen Mary or the United States Lines’ SS America could carry over 1,000 passengers in a single voyage. In the book Custom Inspection of Passenger Baggage, the US Customs uses the arrival of RMS Queen Elizabeth to Pier 90 on May 11, 1949, which included nearly 2,000 passengers and over 6,700 pieces of baggage, as their example. The ideal ratio would be one inspector for every 10 passengers, and on May 11, 159 inspectors were called for Queen Elizabeth.

Left: Officials speaking in a US Customs office], 20th century. Photographic print. US Custom House Collection, 2005.USCH.0399

Right: “Passengers waiting to be processed by custom inspectors at Hoboken Piers”, June 4, 1953. Photographic print. US Custom House Collection, 2005.USCH.0240

It wasn’t just the size of the vessel that was considered when scheduling inspectors: where the passenger vessel was sailing from was part of the calculation. A luxury liner with a large number of First Class passengers coming from Europe could have an abnormally large volume of baggage per person. Since US citizens could be processed more quickly, ships that had a larger number of returning Americans would require fewer inspectors.

Meet and Greet

On the day of the ocean liner’s arrival several Customs inspectors, along with Public Health and Immigration officers, would board a small US Customs cutter, and meet the passenger ship at the entrance to New York Harbor. This gave the inspectors about two hours to go over the passengers’ customs declaration forms before arriving at the pier. The inspectors would look through the forms to flag items or persons they deemed suspicious. US Customs worked with other government agencies like the FBI on lists of suspected smugglers or people of interest. It was not unusual for a large ocean liner like RMS Queen Elizabeth to have 3 to 4 suspected smugglers amongst the listed passengers.

[Officials onboard a US Customs cutter], 20th century. Photographic print. US Custom House Collection, 2005.USCH.0403

If a celebrity was on board the incoming passenger liner, members of the press and official dignitaries would jockey for one of the few extra spots on the US Customs cutter. Two months before Winston Chuchill visited New York, requests from reporters and film crews were already coming into the Custom House. After coordinating with the State Department, the British consul, and Mr. Churchill’s security team, 250 temporary boarding passes were issued and two cutters and a large tugboat were dispatched to meet the ship. The writers of Custom Inspection of Passenger Baggage wryly note that “For the next two hours the battle was Mr. Churchill’s.”

[Passengers arriving in New York City], 20th century. Photographic print. US Custom House Collection, 2005.USCH.0312

Non-celebrities may not have had people greeting them from the US Customs cutter, but they often wanted a friend or family member to meet them at the pier. Getting onto the pier required a permit from Customs and only one person would be allowed per arrival. In the weeks before a liner arrived in New York, the clerks at the Custom House would be handling long lines of people hoping to secure access to the pier to greet their loved ones. On the day the ship arrived, hundreds of people who didn’t get permits would be waiting outside the pier building, on Manhattan’s West Side streets.

Orderly Chaos on the Pier

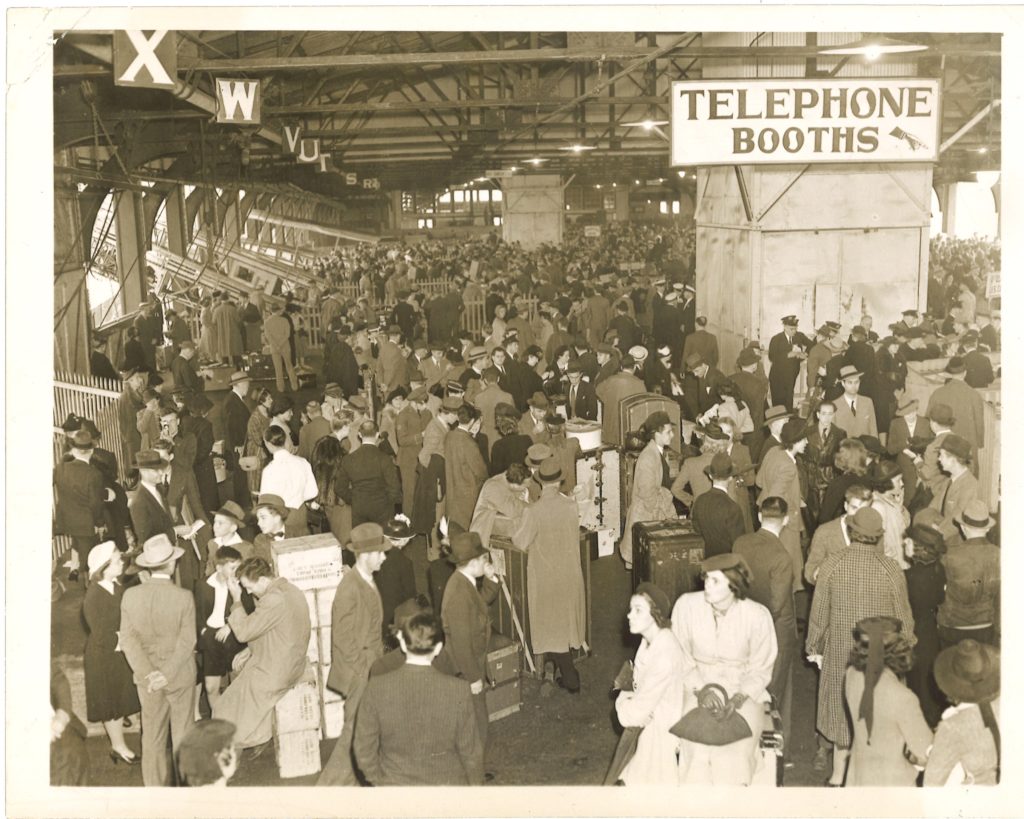

“Pier Jammed as Manhattan docks”, September 7, 1939. Photographic print. US Custom House Collection, 2005.USCH.0261

The moment the gangway connected the ship to the pier, passengers would disembark into a warehouse-like structure. Simultaneously, baggage would be unloaded from the ship, and taken to the Customs examination area by a fleet of baggage handlers and stevedores. Along the length of the pier were large metal signs with the letters of the alphabet. A passenger’s luggage would be deposited beneath the first letter of their last name for them to collect. There were separate sections for First Class and Tourist Class, and the steamship companies usually chose to prioritize unloading First Class luggage. Since the Customs inspectors on the pier examined on a first-come-first-serve basis, passengers in other classes were often frustrated by the apparent preferential treatment by the inspectors. Custom Inspection of Passenger Baggage contends that the inspectors couldn’t force the steamship companies to unload the luggage differently and that “the Customs Bureau is powerless to remedy the situation.”

Left: [Workers unloading baggage from a ship], 20th century. Photographic print. US Custom House Collection, 2005.USCH.0177

Right: “A Scene on the Pier within the Customs Enclosure”, 1953. Photographic print. US Custom House Collection, 2005.USCH.0302

Once a passenger located their bags it was time to wait in line for a Customs inspector. The inspector would check the passengers’ form and ask them a few questions to determine if they had anything additional to declare. Since even a straightforward inspection would take at least 10 minutes, the very last passengers from a large ship like RMS Queen Elizabeth could be waiting up to 2 hours in the pier building.

The writers of Custom Inspection of Passenger Baggage discuss the situation pragmatically, and ultimately argue that there is simply no getting around the wait. In their words, “the wait always appears much longer than it really is, of course, particularly since passengers all too frequently ascribe all of the time spent in the inspection process to ‘Customs’, even though much of the delay may have been occasioned by the Public Health or Immigration inspections or by delay in the unloading of baggage.”

But what exactly were the Customs Service looking for as they processed each passenger and their luggage?

Smugglers and Stragglers

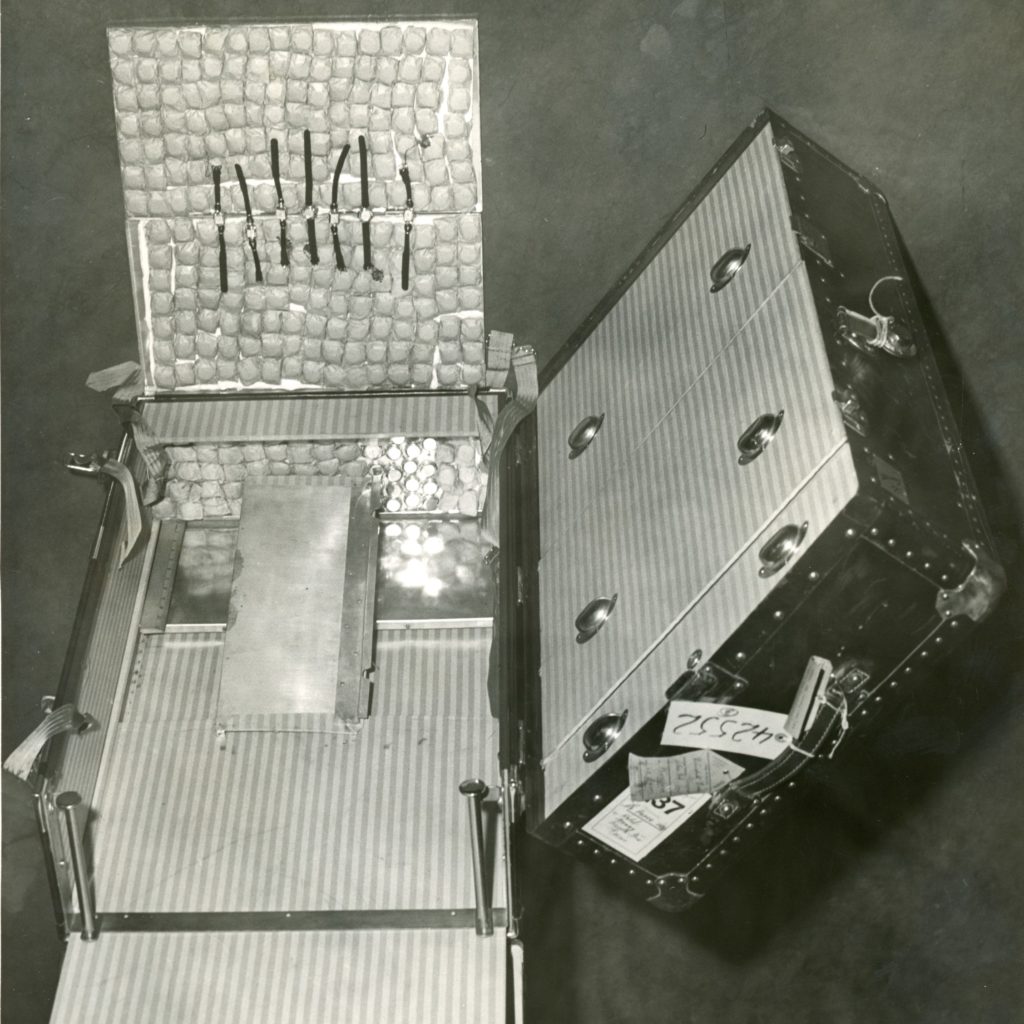

There were two kinds of smuggling by passengers that the US Customs inspectors were responsible for detecting on the pier: the smuggling of (often expensive) goods to avoid import tariffs, and the smuggling of prohibited items such as illegal drugs and weapons. Smugglers could use all manner of tricks to hide items from the inspectors both in their luggage and on their persons. False bottom trunks, gems sewn into clothing, and hollowed out shoes and books were all known techniques.

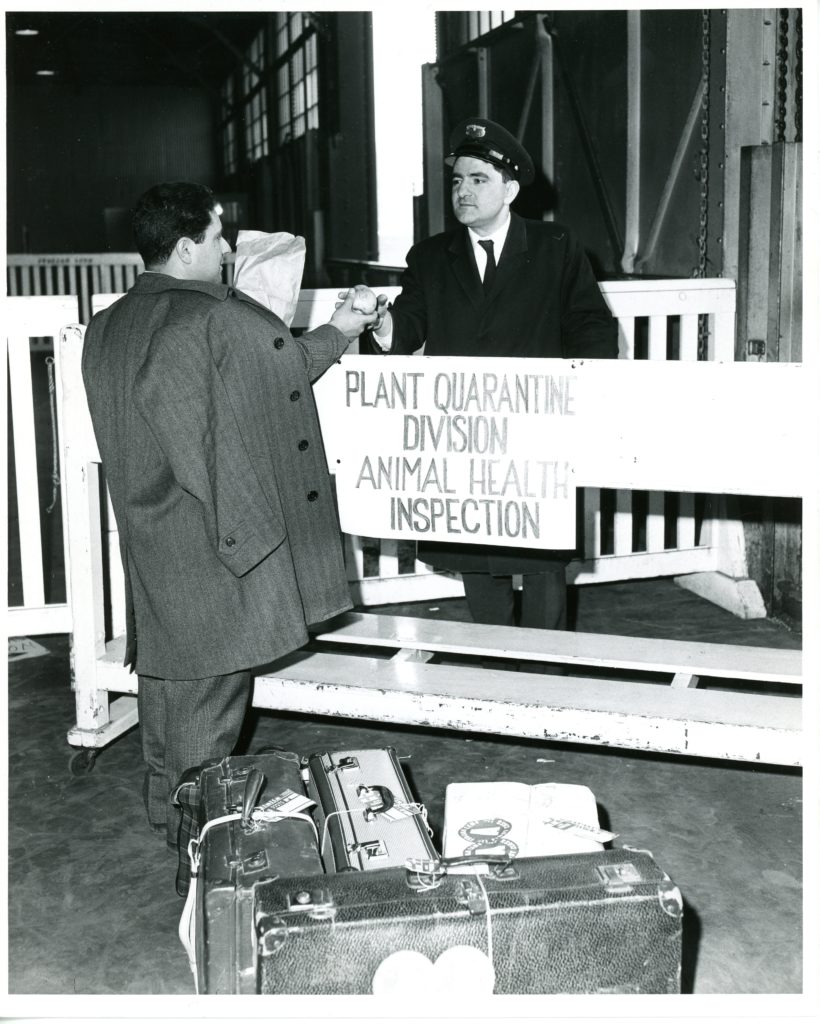

If the passenger had been identified as a possible smuggler their luggage would be inspected with the greatest care. Every item could be removed from the trunk and examined including each article of clothing and opening every jar, box and tube. The largest and most newsworthy smuggling operations might even include paid-off Customs inspectors willing to look the other way. On the less lurid side, the Customs inspectors were also responsible for inspecting plants and animals to prevent disease and pests from entering the country.

“Plant Quarantine Inspection Station”, March 29, 1968. Photographic print. US Custom House Collection, 2005.USCH.0311

At the end of the inspection, the Customs staff would stamp the passenger’s form and luggage tags so that they could depart the pier building. If the passenger needed to pay additional duties or charges they could do so at a cashier station in the middle of the pier. Custom Inspection of Passenger Baggage closes the section on the passenger’s Customs experience with the line “…the passenger is free to descend to the street to search for a taxi; an activity which may remind him that non-governmental operations are also often frustrating.”

The pier building would gradually empty out, with the Customs collecting unclaimed baggage to bring to their warehouses. The following day the extra inspectors pulled from the Cargo Division would return to their regular posts throughout New York Harbor until the next megaliner was due.

Arthur Rothstein (1915-1985), photographer. [US Customs officials inspecting liner passengers’ trunks], 20th century. Photographic print. US Custom House Collection, 2005.USCH.0258

Conclusion

The US Custom House Collection at the Seaport Museum can tell us so much about the Port of New York through the 20th century beyond this one story about passenger arrivals. The Museum has recently digitized and released a selection of 200 photographic prints, dated ca. 1920s-1960s, from the collection onto a free Collections Online Portal. We’re excited to continue exploring the history that these items can illuminate and to work with the National Archives of New York City. Since the collection touches on topics that are still very much part of our modern lives—even everyday experiences like waiting in lines when traveling—these historic artifacts have the power to connect us to our shared past in New York and beyond.

Additional readings and resources

National Archives and Records Administration. “Records of the United States Customs Service”, Guide to Federal Records in the National Archives of the United States.

Burrows, E. G., Wallace, M. (1998). Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. Ukraine: Oxford University Press.

Collecting the Customs: Summary History of the Development of the Tariff in the United States and Its Administration, August 1, 1939, 150th Anniversary of First Federal Tariff and Organization of Customs Service, 1939.

U.S. General Services Administration. “Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House, New York, NY”, Explore Historic Buildings.

Research Policies

Conducting research is a vital part of the Seaport Museum’s work. The Museum is actively engaged in a complete inventory of its collections and archives. This ongoing project will improve future public access to the materials in our care and ensure that items are documented and preserved for future generations.